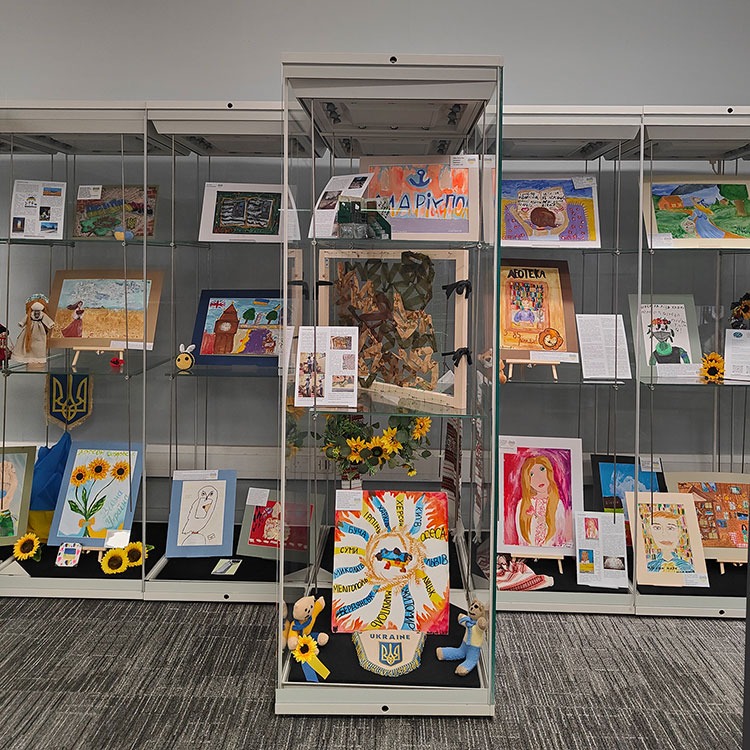

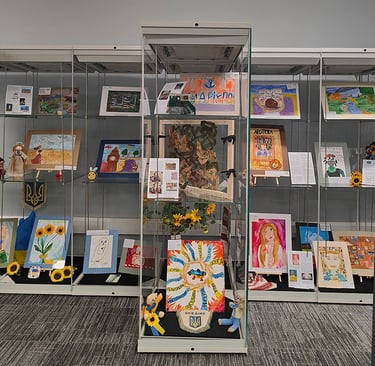

Camouflage net at Edinburgh Central Library exhibition

The exhibition at the Edinburgh Central Library starts today and one of the items on display is a camouflage net made by a 6-year-old child, Anya. This is the story of the net.

Anca Marin

10/4/20254 min read

I first saw Anya weaving nets while an air alert was on. It was upsetting to see a girl of her age so unfazed by the alerts, in a city which is much safer than the one she was born in, but still not completely safe. Anya is 6 and she fled from Kharkiv with her family after russia’s full-scale invasion.

The family settled in Lviv since 2022 and her mother has started volunteering. Anya, a very bright child and eager to help, learned how to weave nets and works alongside her mother. The method of weaving is complicated considering the number of colours and the rules on how to make them effective, both in terms of sturdiness and ensuring coverage. To get to the centre by_porokhova, Anya and her mother need to travel for an hour or more. Thus, they are doing also kikimoras [full body camouflage] at home.

This is only one of the stories on display at the Edinburgh Central Library. Visit the exhibition to find out more about the children of Ukraine.

I was impressed by how well she makes the nets. As a volunteer at that centre, who was also asked to teach some of the foreign volunteers when the lady who is in charge of this was not there, I know first hand how much time, patience, and dedication it takes to make the nets as well as she does. I could not have faulted her net. I asked Anya and her mother if they would be happy for Anya to make a net to display in Edinburgh. They, very kindly, agreed. The following day they travelled to the centre and Anya weaved this net for me. It was made on a frame usually used for making covers for helmets.

The centre by_porokhova opened in 2014, when russia attacked Ukraine. They are producing dozens of nets each week, working six days a week, and welcoming hundreds of foreign volunteers, who work with many Ukrainian volunteers who are coming weekly.

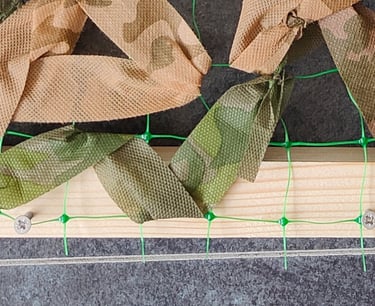

It was important to make sure that we are representing both her work and the work of the other volunteers at realistically. The frame was made to match the ones the centre has for the big nets. All details were considered: the wood is left untreated, the cut for joining the frame is straight and not at a 45% angle, as it would have been with a frame. This is a piece of art, but also a piece of war, and accuracy is more important than beauty.

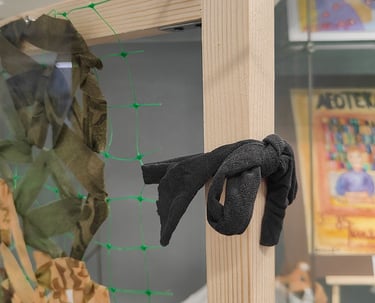

The method of hanging the net to the frame is also similar to the one used in the centre, a mix of nails and fabric. Nails are used for nets that have the same size as the frame, the plastic is stretched on the frame, and the camouflage cloth strips are woven on it. If the nets are smaller or longer, some ribbons of fabric from old clothes are used. The net we displayed in Edinburgh is a mix, nails for the lower part and some black fabric from an old T-shirt cut in strips. I did not want to use a new ribbon because it would not have been accurate. Some of the dozens of camouflage making places in Lviv use old clothes and other types of fabric. It saves on having to fundraise for the specific camouflage cloth. The only difference is that the pieces of fabric are tied into a bow. It is a reference to the beautiful ladies who are weaving. They like to dress nicely, have their nails and hair done. The war is going on and being true to themselves is a way of resisting against the aggression.

The frame was put together with no glue and using lightweight brackets. It is a rough frame, just as the ones in the centre are. It is mimicking the urgency of war, making frames like these fast, to be able to produce nets for the soldiers at speed. In the Summer, the centre has an extra frame placed in the corridor, 6 metres / 20 feet in length. That is dismantled in the academic year, as the centre is located in a theatre that has some art classes for children. The frame on the corridor appears again the following Summer.

Anya dreams of returning to Kharkiv. She wanted very much to start school at home, a place which she misses a lot. But Kharkiv is not safe, and children learn in underground schools. In September, Le Monde reported that there are not enough underground shelters for children to study. Two-thirds of children aged 6 to 17 are learning online, despite the city having seven underground schools, six metro stations serving as schools, and five Soviet-era bomb shelters converted into schools. Reuters reported that 17,000 children in Kharkiv are attending underground schools. Kharkiv is Ukraine's second-largest city, with more people coming in from areas which are even more affected by constant attacks. For the month of September, when children started school, throughout Ukraine, there were over 700 air alerts, on average lasting over an hour and a half.

Anya was taken to school by her mother, hand in hand, wearing beautiful Vyshyvankas, not in Kharkiv, but in safer city of Lviv.

Contact Us

Donate

Would you like to donate?

Any donation is gratefully received.

Thank you.

Please click the link below for our donation information.